.

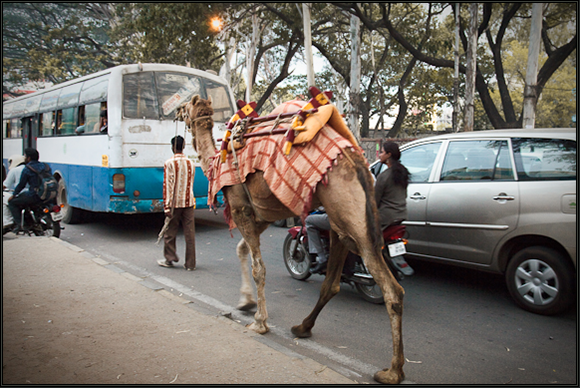

Normal traffic standing outside the Adobe office in Bangalore.

Archive for May, 2009

Curbside At Adobe

Kumkuma

.

Venu came running up the front steps with a handful of red powder and a wooden stem broken from a stick of incense. He went around to the side of the porch and ran some water from the spigot there into his hand and came right back, looking like he was bleeding from an artery, speaking at me in rapid-fire Telugu and pointing frenetically at my forehead with the stick.

This could only mean one thing: it’s time for a makeover !!

He dipped the stick into the thick red goop in his hand; then deftly pressed it to my forehead and removed it again in a single motion, leaving behind this perfectly vertical red mark.

The red stuff is a powder called kumkum, but Venu and his family call it “kumkuma” as they speak Telugu. These marks are, as I understand it, primarily a Hindu custom, and it originated long long ago with blood sacrifices. As messy animal sacrifices became less fashionable, the powdered kumkum eventually took its place; serving the same wide variety of purposes, but without making so much noise. The velvet adhesive dots of various colors and the jewelesque adhesive Bindis are also descended from the same origins. Anyway, these particular kumkum marks indicate to which of the many manifestations of the Hindu goddess you are devoted; in the case of this single vertical line, I think it indicates devotion to Shakti and/or Lakshmi. And though this is a primarily Hindu thing, forehead decoration in general here is for anyone to enjoy.

There’s a Place in Hell for People Like Us

It is Saturday morning, and the baby at the construction site next to our house won’t shut up. OK, maybe that’s an exaggeration: he’s not baby, he’s a toddler.

They’re building a three-story shopping center in our quiet, by Indian standards, neighborhood. The site has been a riot of chaos for a month now. Overlords in mirrored glasses overseeing a sari-clad chain gang. On most days the hideous grind of the cement mixer drowns out the crying children. Toddlers. Whatever.

At night, most of the workers go home, but dozens stay and crowd into the pair of cinder-block shacks that were built when the construction first started. I’ve heard that these builders are nomadic families who travel from one project to the next for six months or a year at a time. The children play in the sand piles until they are old enough to carry cement on their heads; apparently around age four. The ten-year-olds cook for the families on open fires, inside the shacks, breathing in black smoke… while my husband and I lay in our canopied bed, in our air-conditioned bedroom, complaining about the crying baby, and trying to forget that it looks like a UNICEF commercial is being filmed next door.

Rat. Parkour. Kitchen.

.

Last night there was a rat in the kitchen. He didn’t have the long slithering black Manhattan-trash-pile-on-the-hot-summer-night tail that makes me want to scream and pass out; he was more like a giant-sized field mouse. A Beatrix Potter creation with soft brown fur who would have been perfectly at home sitting on a pin cushion reading the newspaper. But still, he was a rat, a five-inch long disease-carrying rat… apparently built on springs.

The rat launches himself from the table, bounces off the back of a chair then flies to the window five feet away, scrambles up the blinds and disappears. By now my screeching has gotten Phil’s attention: “We have rats !” I shout, as he hurries downstairs. “Rats – BIG rats,” I point at the window blind.

Phil grabs a paper bag, I grab a cow whip that the maid laughed at me for buying. I whap at the blind while Phil stands ready to catch the varmint in the bag. I whap again: nothing. I open the blind then let it roll open.

Phil sees a shadow dash into the kitchen on the other side of the room and shouts, “Fucking hell, that’s a huge rat !” We run into the kitchen just in time to see him slip behind the fridge. Phil muscles the fridge away from the wall. The rat darts across the floor to the water cooler. We scream like seven-year old girls.

I smack the water cooler. The rat flies over the microwave to the towel rod below the cupboards. He scampers the length of the cupboards. When he gets to the stove he leaps three feet to the window, and scurries to the top of the blind. Cow whip – check. Bag – check. He peeks at us over the top of the blind, and we’re pretty sure he’s laughing, great peals of silent rat laughter, because this is hilarious. The two of us are doubled over, howling.

After seeing this rat in action, both of us know we haven’t got a chance in hell of catching him. It is impossible not to be impressed. He may be the most efficient being we’ve seen in this country to date, the first creature who appears to know exactly what he’s doing (in this case, evading his captors), and is going about it in the most ergonomically streamlined way possible (see “parkour” in the Wikipedia; or watch the opening sequence of Daniel Craig‘s James Bond movie, “Casino Royale“).

I tap the blind and he launches himself from the top of the window into the sink full of dirty dishes. He bounces from a soup bowl into a saucepan, then tumbles over a tea cup. Our kitchen has become an Indian Tom & Jerry cartoon, a live rat theater production of Ratatouille. He escapes and we can’t stop laughing.

Phil and I look around the kitchen. “Of course we have rats,” he says. “Look at this place.”

Dishes in the sink, trash on the floor, food on the counter. The maid doesn’t really get the whole “clean” thing. She is great at mopping the floors, but seems to be baffled by things like glass counter-tops and emptying trashcans. She’s nearly as bad as I used to be at doing the dishes directly after dinner. Phil and I have trained ourselves not to complain about each other, so we forget to complain about her.

The maid and I need to have a talk.

Lizard Luck

.

Bhaskar says geckos are considered bad luck in India. We have loads of them, so who knows what that means… but he also says if you are a man, and a gecko falls from a tree onto your right shoulder, it is good luck; for women, if the gecko lands on the left shoulder it is good luck. Anywhere else and it’s bad. Very, very bad.