Continued from Part One.

After the disappointment of off-season Anjuna, we decide to make our way south again to Palolem, and from there catch a bus back to Bangalore a day early.

.

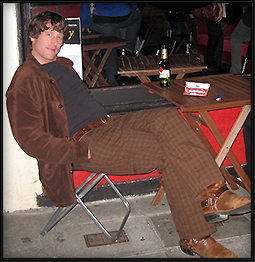

Back on the Enfield, the coastal road gets wetter and wetter by the mile. Firehose torrents soak us from above and below and both sides at once. I take off my helmet and slip it onto Phil’s head. We have one helmet between us. We’ve been looking for place to buy a second helmet for days now but have found nothing. I am more afraid of head injuries than he is, so I keep it on my head until the rain becomes too fierce and Phil can’t see without the face shield. We are soaked to the bone and don’t have anything dry to change into anyway, so getting dry and waiting out the storm isn’t a possibility. There is really nothing to do at this point but to laugh and keep rolling – at least the water is warm.

![]()

.

This trip has been about the ride, more than anything; about the freedom of movement through time and space. Unlike in a car, on a motorcycle you become part of the landscape. You see things: expressions on faces, goats, children, other bikers. You feel things: the air, the rain, dust and exhaust. You smell life going on around you and can feel your own heart beating in your chest as the adrenaline moves your blood faster.

If I’d have known being a biker chick was so much fun I’d have scored a leather halter-top and hooked up with a criminal biker years ago. If Phil had known how natural riding felt, he might have become an outlaw instead of a UI designer. Together we would have been unstoppable, and it would have been disastrous. It’s good that neither of us have discovered this passion until now.

We feel like children splashing through mud puddles as we swoop along the flooded road. We are on the lam, racing toward the unknown. If there are rules, we don’t know them. If we knew them, we’d ignore them.

I’d always thought that the notion of motorcycle-as-freedom was just kitsch made up by an ad firm, but that was before. Before I’d traveled on a bike, before I’d felt my thoughts untangle and the layers of obligation and frustration and worry blow off my skin and disappear in the wind. That was before I understood that being on a bike, even sitting on the back, is a meditation – a time of single, simple focus.

![]()

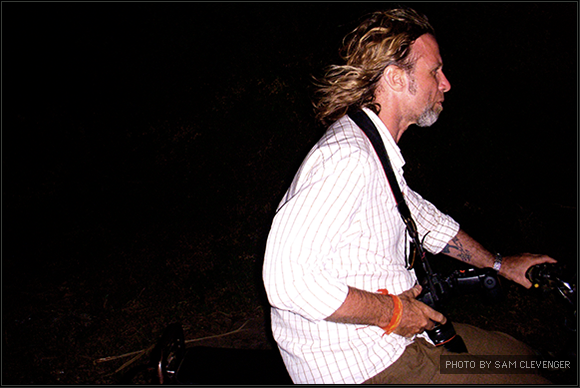

Perhaps Phil and I revel in this feeling of freedom more because in India our freedom is so severely limited: limited by culture, limited by language, and limited by our driver, Mustaq.

.

Mustaq’s job is to get Phil to and from work, and to drive me on errands, and whatever else we need. Getting from place to place in India can be difficult and dangerous for Westerners to undertake on their own, so there is a very real need for this kind of service. And Mustaq, like every other professional driver in India, considers it his solemn duty to let no harm befall his charges. What he sincerely sees as doing his job – arguing with our landlord about our water bill, making sure I choose the best papaya, insisting we use his own trusted Enfield mechanic so that “no ones will take adwantage of you peoples” – a service we once could not have survived without – we increasingly experience as intrusion.

Because taking Phil (or “Sir”) to work and back takes up only about two hours of his workday, the rest of the day he chats on his cell phone or naps in the car outside the house until I need him for my various housewifely errands. I feel somewhat pressured to validate his employment, so instead of walking to the market, I ask him to take me. Yet, each time I get in the car there is resistance: If I say I want to go to Food World, he tells me that Niligri’s is better. If I ask to be delivered to Hypermart, I get, “Oh no, madam, that is beddy teddible place. They will charging you so many hundreds of money.” If I want to drop my clothes to the ironing man down the street, he warns me, “Oh no, madam, that man is beddy beddy horrible person. I tell you which iron man for which you go to.”

Ironically, though Mustaq’s job is intended to provide us with necessary freedoms, the reality is that he has become our babysitter. This makes us feel like children, which in turn makes us behave like children: we routinely lie to him about our plans and sneak out to take tuk-tuks, which he insists are all driven by drunks, to marketplaces he insists are all too dangerous.

![]()

We turn off the main road in Benolim, continuing down the coast towards Palolem, and spend the night at a beach cottage that is so damp the mildew stings your nose. We watch TV for about ten minutes before the power goes off, and stays off for the rest of the night.

I can’t believe how much water is falling out of the sky. I know this kind of rain from when I lived I the Santa Cruz Mountains; this is the kind of rain that floods the creeks and washes cabins down hillsides. This is the kind of rain that knocks out power for weeks at a time.

The rain keeps pounding on the roof while I scroll through the emails on my iPhone: we’re missing parties and weddings, and a chance to make $5000.00 a day while working at home; my mom wonders where I am, and Bill is getting sicker. The dog trainer sends me snapshots of Kali to prove she’s still alive and well. To me they look like hostage pictures. My darling puppy is standing on dirty cement, with metal bars in the corner of the shot. She looks strong and mean.

.

At the last minute, before we began this journey, we had needed a place to leave our puppy, so I tracked down a kennel that I prayed was reputable. That’s how we do it in India: hard facts are often impossible to obtain, so prayer is the only option. I say a prayer, to no god in particular, but knowing how Muslims feel about dogs, I keep Allah off the list. I noticed that the kennel also offers dog training, and since it is painfully obvious by the way Kali still pees wherever she wants and raids the garbage can every fifteen minutes or so, that neither Phil or myself is really has the temperament or follow through to train our little ward. I made arrangements and handed over a fat wad of rupees to upgrade from puppy boarding to puppy charm school.

Since then, we’ve been worried that this might have been a really bad idea: India is a country where no one stands in line, no one says please, no one says thank you; people burp in public and spit and piss anywhere they want. These are all things Kali is already quite good at. I worry that she is being kept in a metal cage with three other dogs, like the chickens at the chicken stall, or left to wander the streets for days foraging for food, like the scrappy street dog she was born to be. The pictures on my iPhone do nothing to assuage my fears.

![]()

The next morning we climb back on the bike, and the rain is falling harder still. The drops hit our faces like bullets. We pass palm trees and rice paddies that are a shade of green that only exists in India. We cross a river where the water is dangerously close to the bottom of the bridge. Water buffalo lie down in swamps that are becoming lakes. Crows hide under tarps. We laugh the first time we plow through a massive puddle because it feels like someone is throwing buckets of dirty water at us.

.

Phil and I both love extreme weather. We’ll stay up late watching documentaries on hurricanes and cyclones. I’ve always claimed to want to see the sky turn pea green just before a tornado lands, but now I silently rescind all that. I close my eyes and bury my face in Phil’s back so the water will stop hurting me.

![]()

We’ve been traveling for hours now without seeing another vehicle on the road. In a nation of over a billion people, empty roads should be a red flag for us; but no, we are too busy enjoying having the roads, and the increasingly violent storm, all to ourselves.

While heading down the mountain pass we roll through a body of water that is much too large to be called a puddle. The murky orange-brown liquid comes past the center of the wheels. We both lift up our feet to stay dry, which is ridiculous. Then, after days of steadfast service under terrible conditions, our Enfield decides she’s finally had enough; she simply stops without warning.

We pull off the road, I untangle myself from the bags that are squished between us and climb off the bike into the mud, stumbling backward from the weight of the camera equipment strapped to my back. We make a run for a rickety blue building, the only structure in sight, to get out of the rain – again ridiculous, considering where we’ve been and what we’ve been doing for days now. We slide down the mud walkway under an awning, and see a collection of half empty liquor bottles behind glass as we draw nearer.

.

A dwarf, with some kind of palsy, limps out from behind a counter that is nearly as tall as he is. He greets us with a huge smile, and welcomes us into his bar: a room the color of a nicotine stain with a shirtless old man in the corner drinking brown liquid and watching the cricket match on a tiny TV.

“What is your native place?” the palsy dwarf asks.

“Amedicka,” we say in unison. We’ve learned that mispronouncing the name of our country is the only way to be understood.

“Ah, Amedicka. U.S., beddy good place. Near Australia, yes?”

We smile and nod. I toss our bags in the corner and pull the off the smurf suit. Underneath my clothes are soaked and clinging to my skin.

“Vishky?” he asks.

“Tea.” Phil says, “is it possible to get some tea?”

He shouts to someone in the back, and then motions for us to sit down, at a table that is dotted with houseflies. He introduces us to his mother, who brings us hot, delicious chai tea; and to his disarmingly pretty young wife; and two gorgeous, grubby children. His five year-old son is nearly the same height as he is. I chase the boy around the room roaring like a monster in my dripping wet clothes while Phil tries to figure out what to do next.

We have no idea where we are. Both our phones are dead, and we really have no idea who to call anyway.

If Mustaq was here, he’d know what to do.

Continued at Part Three.