About a month ago, around the time Bhaskar’s two daughters were headed back to school, I asked what was happening with Harish, our maid’s young son, and why he wasn’t returning to school as well.

“Essaaa… probably next week, ma’am,” Bhaskar answered, unconvincingly.

![]()

Harish is our maid Rathnama’s son. During the school year he lives in this native village in the next state over, with his aunt and uncle, while his parents work here in Bangalore. Harish just turned 13, but we don’t actually believe it. His mother Rathnama doesn’t know her own exact age, but thinks she is around 30. Harish’s sister Gotimine is either 17, 18 or 19, depending upon who and when you ask. And Gotimine’s baby doesn’t yet have a name, but they are quite certain that he is six months old.

I know all this because all summer long there has been a revolving collection of Rathnama’s relations bouncing in and out of our lives. There were a couple of weeks when there were six people in her quarters, which are criminally small for even one person, and a few more sleeping on our kitchen floor.

I can’t explain how this happened, or why we allowed it, or why I bought them sleeping mats so they wouldn’t have to sleep curled up on a cold stone floor. This whole mess is just one of the many cross-cultural mistakes we’ve made so far this year. By the time Harish was the last remaining guest, we were so happy for the decrease in population that we just let it slide.

![]()

Now, another month has passed, and I am weary of seeing Harish’s grinning face peeking at me around corners when I least expect it. “Can I watch TV, auntie? Can we swim now, auntie?” Phil and I are both very fond of the boy. He is sweet, well-mannered, and like all the Indian children we encounter, undeniably adorable. But what started out as a pleasant visit has turned into a haunting. When I finally realized I was spending half of every day hiding on the roof in a lean-to I’d made by pinning a bed sheet to the clothesline, I knew it was time to cowboy up and reclaim our territory.

I thereafter made it clear to Bhaskar, who then may have made it clear to our maid, that no more guests were allowed to stay in her quarters. No friends, no family, no one. We did everything short of posting house rules on the fridge. The message seemed to get out, and Bhaskar even stopped napping in our TV room when I was on the roof.

Yet, another week went by and still Harish was in our house.

![]()

“So, Harish,” I said. “When do you go back to Puttaparthi for school?”

“Um, Tuesday or Friday I think, madam,” he says.

I know this means that he has no idea. I pull Bhaskar aside and ask him if he knows what’s going on with Harish and school. I say this in a tone that I hope will clearly convey that we are really and truly done having people in the house: drivers, children, the drivers children, the maid’s children, everyone.

He rattles off an incomprehensible sentence:

“Essaaa… Money pdom delations dey adr waiting podr.”

I know Harish’s family is in a grave financial situation. A couple of years ago, back at his native village where his family owns farmland and houses, his father had co-signed a loan that the other party apparently defaulted on, and now the lenders are after them. Harish’s parents have moved to Bangalore to take jobs to repay the debt: Rathnama, as a maid in our house, and her husband as a night guard at a construction site up the street. The best we can tell, it will take them years to earn enough to pay what they owe.

“How much does school cost?” I ask Baskhar.

Instead of just answering me, he calls Rathnama, her husband, and Harish into the dining room. A ten-minute mystery conversation takes place between the four of them, periodically punctuated by them each briefly looking over at me.

“Baskhar, how much do you pay for your children’s school?” I ask, trying to clarify my original question.

Bhaskar plays an important role in our India life. He’s not just our driver, he is our self-appointed nanny, guardian, and translator. The problem is, he doesn’t really speak English. He does, however, speak the local languages of Kannada and Telugu, which the maid and her family speak; and, as limited as his translation skills are, they are indispensable.

“Ma’am,” Bhaskar says, “They bring you billett with itemization.”

I tip my head like a dog trying to understand.

“Okay…” I say, tentatively. “Maybe we can contribute for his books, or uniform, or something.”

The way this whole thing is unfolding sends up a thousand red flags and I am extremely uncomfortable.

“Okee, okee. They bring bill. If you and Sir want to pay a portion, you pay.” He wobbles his head in a dismissive way.

The matter is forgotten by morning, and we take off traveling for a couple of weeks.

![]()

We arrive back home from our travels, happily exhausted, in the pre-dawn hours of a Monday morning, to find Harish in the entryway, standing at the ready, smiling wide.

“Good morning Auntie, how are you Auntie?”

“Harish, what are you doing here?” I try my best to sound cheerful.

He hands me an envelope.

“Here is billett for my school, Auntie.”

I am so not ready to be thrown into this pool yet. I’ve just spent ten days decompressing from the dramas of my de facto household, and enjoying the lush freedom that comes when your every move isn’t being observed. I have a chest cold, and there is no caffeine in my blood stream.

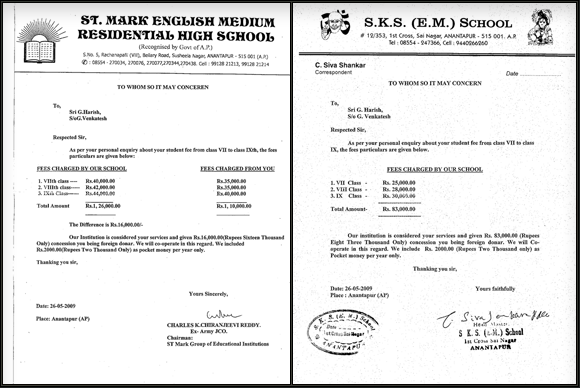

I take the envelope from Harish and open it while my tea is brewing. He watches me as I pull out two letters addressed, “To Whom it May Concern,” out of the envelope. I scan the letters and see that they are from two different schools. One is an invoice for 160,000 rupees, (around $ 3,400) and the other for 120,000 (about $2,500).

They are invoices for three years of boarding school.

I am too shocked to edit myself:

“We can’t pay this, Harish, it’s too much money !”

I feel terrible. And to make it that much worse, I can see from the look on this child’s face that he fully expected me to whip out my wallet and hand him the cash. He’s putting on a brave face, but I can tell he’s hugely disappointed. My stomach is tight and I can feel my swirl of confusion threatening to turn into tears.

![]()

I walk upstairs, lie on the bed, and stare at the ceiling. These people have so little, and this child has no future without an education. I see it all around me every day: promise turned sour and a life spent in resignation pushing a mango cart or smashing granite into gravel at the side of a road somewhere. These people want the same thing anyone wants: for their children to do just a bit better than they did. But here in India, the infrastructure isn’t keeping up with the population. This is a country where still only 17% of the population has access to a toilet, where 42% of the children are under nourished. 70% of the marriages are arranged, and the people in villages, which is 80% of India’s population, still think it is okay to marry your first cousin.

“What are you doing ?” Phil comes in and sits on the edge of the bed.

“Harish just gave me these,” I say, and hand him the letters. “It seems they think we’ve offered to pay for three years of boarding school.” Again, I’m on the verge of tears.

“And did we?” Phil asks.

“I don’t think so. All I did was ask how much school costs. I didn’t offer to pay,” I say quietly. “We can’t pay that. We can’t afford to pay that even if we wanted to.”

Phil reads the first letter out loud, and pauses.

.

“Does anything seem strange to you about these letters ?” Phil asks.

“Let me see those again.”

I scan through the letters, and it becomes perfectly clear that the two invoices are suspiciously similar. There is slightly different formatting but with the same comically garbled English and the exact same misspellings. In fact, if I’m honest, these letters look a lot like Nigerian spam.

“These are totally forged,” Phil says, smiling.

“No… !” I say. “They wouldn’t do that.”

The thought that these people, who we have come to trust, are trying to scam us, is hard to swallow, and I spend the afternoon on a mission to prove that we are paranoid freaks. I try to get through to the phone numbers on the letterheads. Four out of four do not work. I read both the letters over and over again and try to find something, anything, believable about either one.

I speak again with Rathnama, Harish and Bhaskar, trying hard to find some scrap of mitigating clarity: I ask, as clearly as I can, where Harish would go to school if we could not pay for one of these places, and suddenly, between the boy and the driver and the maid, a fact spills out: the child is already enrolled in another school. This tiny, though meaningful, item serves to solidify what I’ve been trying hard not to see for the past several hours; my disbelief drains out of the equation and it becomes all too obvious.

“Oh, my God… this whole thing is just a fucking con,” I shout, clutching the letters in my hand like an irate newscaster.

“You think you can just type up some letters in bad English and we’ll hand you four thousand dollars ? In America when people pull crap like this we call the Hell’s Angels – or the police !”

I storm out of the room, but keep shouting, off-camera.

“Do you people really think we are this stupid ? We are not giving you a goddamn penny, or rupee, in fact you’ll be lucky if you still have a job and a place to live by morning !”

I stomp upstairs and look at the letters again, without filtering the words through my white guilt. And it becomes obvious that his ham-fisted con has all the craftiness of a fifth-grader forging a report card.

The whole situation has knocked the wind out of me. For the next three days I hardly leave the bedroom and I barely speak. I am devastated. I cry on the phone to my dad like a homesick seven-year-old at summer camp. I want to go home. I want to be someplace that I understand.

I fantasize about sitting the whole group down and telling them the story of the goose that laid the golden eggs, and explaining that sound they hear… that is a goose’s death rattle, and the sound of my wallet not opening.

Rathnama plays dumb. She swears she doesn’t know what is on the fake letters, but the way she is shamefully moving through the house cleaning things she never seemed to even notice before, tells me she knows exactly what’s up; although, I doubt her knowledge really makes her complicit, because, as an illiterate Hindu wife, she doesn’t wield much power.

While sulking, I replay the events of these past four months and realize that it is our good nature that has made us such easy marks in the first place. These people truly think that we are rich, and arguably it is my fault for giving them that impression. If I were from a village that raised goats and grew peanuts, and just stumbled into our house and saw the swimming pool and climbing wall and three extra bedrooms, I might come to that conclusion as well. The fact that I took the whole family to the zoo for Harish’s birthday, that I’ve bought the baby some clothes, and Rathnama saris and sandals, and Gotimine an armful of sparkly bangles, just helped to paint a certain picture.

The fact is, we are in India to save money for a down payment on a house when we go back home to San Francisco. Even though Phil and I have little debt, we actually own nothing, have nothing saved, and there is one more child to get through college.

We are not rich: we are stupid.

![]()

A couple of days later, the cement mixer at the job site next door fires up under our bedroom window at 7 a.m. and wakes me out of a sound sleep. I’m pissed because right now all I want to do is sleep. I pull on a robe and march downstairs. I lean over the fence and look for the guy in the sunglasses talking on the cell phone. He’s promised to move the mixer from under my window three times now, and I am ready to rain crazy white lady all over him.

Four women are carrying cement on their heads from the mixer to the foundation they are building. A small child follows one of the women, pulling on her sari and wailing mournfully. She keeps walking, balancing her load while she climbs barefoot through rubble and dirt, ignoring the child until she dumps her cement, then picking him up and carrying him back to the mixer where she waits for the boys to shovel more wet cement into her head-tray. She sets the child down and he wails and tugs on her sari. They repeat this routine over and over.

The woman works this way every Monday through Saturday. On Sunday, she does her family’s laundry. Scrubbing and smacking the cloth against the cement wall that her sisters have already built, then drying it across pieces of rebar. She and several other people, with several other children, all live on the job-site in a cinder-block shack with a corrugated metal roof held in place by large rocks. The children spend their days playing in piles of sand that will soon be turned into cement.

I watch these women working harder than I’ve ever worked in my life, and know that if I were in their situation, I would absolutely do anything I could to get my child an education, with the hope that someday they may be able to rise above this grueling life.

Rathnama and her family, though slightly better off than these laborers, are no different. And I realize that I’ve been taking this whole thing way to personally. I did everything short of thievery and extortion to get my own daughter a good education. If I were in their situation, I might have done the exact same thing.

I do like to think I’d have forged more convincing documents.

![]()

Days have passed by now, and Harish is still lingering around the house, though less omnipresent than before. I hazard the same question to Bhaskar that started this whole mess:

“Why isn’t Harish in school yet?”

“They waiting por monies from relations before to send him on bus for school in native place.”

Pause. Thinking.

“Bhaskar… How much does Harish’s school really cost ?” I ask.

“Just ten thousand rupees ma’am, for one year.”

![]()

“Honey,” I say to Phil later that night, in that tone that means I am about to say something unreasonable. “Guess how much school really costs for Harish?”

“How much?”

“Two hundred dollars a year. Bhaskar told me.”

“And how do we know he’s not lying too ?” Phil asks.

“We don’t.”

Sadly, this is true. Both Phil and I now suspect that all of India is lying to us all the time. There’s always the chance that Bhaskar was in on the con as well: after all, he and Rathnama are thick as thieves; they chatter endlessly in their bouncy languages; she even cooks for him and washes his clothes. If this weren’t India we’d suspect impropriety, but things like that just don’t happen here.

Finally, we decide that ensuring Harish gets his education this year is worth a two hundred dollar investment, especially if it means getting our privacy back.

But we won’t get fooled again:

We confirm that the school is real; we confirm the costs of books and lodging; we confirm that the phone numbers work and that the people who answer do in fact work at the school answering phones.

To further ensure everything is on the up-and-up, we arrange to have Bhaskar personally deliver Harish to his new school in Andhra Pradesh. We give him five thousand rupees, enough for six months’ tuition, which we instruct him to pay to the school’s headmaster directly. We will return to the school ourselves in six months to pay the balance in person.

Bhaskar and Harish leave at 6 a.m. the next morning for the four hour drive to Andhra Pradesh. The following evening, Bhaskar returns, sleepless, unshaven, and thankfully, alone. He places a signed receipt and a payment booklet from the school on the table, tossing us a tired smile and half a head-wobble.

“Beddy good school, ma’am. Harish beddy happy.”

He really better not be lying.