.

We like to keep our front door open to let in the light, and to let Kali out, although it seems to be the signal to the neighborhood that we are accepting visitors. The neighborhood kids have gotten so comfortable coming in that if our front door isn’t open, they poke their heads through the bedroom window and ask, at the top of their lungs:

“Are you sleeping, Auntie?”

“Stop looking in our windows,” I shout from a half sleep.

“I’m just seeing if you’re sleeping, Auntie.”

“Yes, we’re sleeping. Looking through other people’s windows is rude.”

“Sorry, Auntie. I’ll come back later, Auntie. When should I come back?”

An hour later he shows up in my kitchen.

“Why aren’t you in school?” I ask.

“We had a picnic at school yesterday. The head mistress told us to stay home today and rest.”

Every week these kids seem to have one or two days off, for “Teacher’s Prayer Day,” or “Children’s Day,” and now “The-Day-After-We-Had-A-Picnic Day.” The list goes on and on, and probably explains a lot about the sorry education these kids seem to be getting. In any case, a day off of school means that they’ll probably be lurking around, in and out of my hair, all day long.

A few months back we moved from the hellish palace at Panduranganagar, with the four bedrooms and the built-in swimming pool and the rats and the cast of Ben Hur, into a simple two-bedroom flat in the sweet, sweet neighborhood of J.P. Nagar. Our arrogant landlord’s parting gesture was to attempt to wring another five thousand dollars out of us by falsely accusing us of stealing and breaking a long list of things. Phil and I were insulted beyond belief and responded with letters that likely caused his computer to burst into flames when he opened the emails. His response to our response was to threaten to have us arrested. Our response to that was to laugh. We never paid the money and we never got arrested. Such is India.

.

Our new place is what they call a stand-alone house, even though there are four units in the building. According to India, we are on the second floor; according to logic, since we have two floors below us, we are on the third floor – that is, unless you find it logical that the number “ground” comes before the number “one”. Up here, we are at eye level with the giant trees and close to the rooftop and the eagles. It’s a quiet street with no construction, no truckloads of gravel and sand being dumped out into massive piles, and then scooped by hand into a cement mixer two feet from our bedroom window. Our house has no rats and no live-in help.

Our new neighborhood is like America in the 1950’s, and we are like the first black family on the block. Watching us go about our business provides people in balconies up and down our street something to do; and by do, I mean stare. I get the feeling we confuse them. They are kind, but wary. They seem utterly amazed that we need to wash our clothes, buy groceries or walk our dog.

Phil and I are the only people who live in our new house. It’s hard for the locals to understand why we would want to live in such isolation. Here, people live collaboratively. Groups move as one organism. It works for them, and we gave it a shot, really we did: we had a maid, and a cook, and pool boy, and a dog walker, and a full-time driver, like many Indian and ex-pat families.

In India, labor is cheap, but that cheap labor often comes with a price tag much higher than the wage would suggest. For 100 rupees a day you can get someone to turn your white clothes gray, hide things in closets you didn’t know existed, and use your new cloth napkins to wipe out the inside of the trashcan. Someone who will walk into your bedroom unannounced and sweep under your bed while you’re having a sensitive conversation on the phone. Someone who will lie to you about when they walked the dog, and who will attempt to extract money from you whenever the opportunity allows.

Aside from all that, our biggest challenge has been the lack of privacy. We are Americans, and it is impossible to explain just how much we need our privacy, and just how much we dislike having our every move watched, dissected, commented on, or corrected; just how much we enjoy and need solitude.

Phil and I may need those uncrowded moments more than most. For each of us to work, we need time to dream, to stare into space, time to try uncertain things, and we don’t need seven people watching us when we fail. All these quiet moments disappear when there is someone sweeping under your chair, or needing you to celebrate a birthday for the neighbor’s child. Phil compares his work process to spinning plates: once you get them all up there spinning, and someone or something breaks your concentration, it can take hours, or days to get those plates up in the air again.

Also, where we come from, self-sufficiency is a virtue, a concept that doesn’t appear to work in a nation of over a billion people. Americans pride ourselves on being able to carry our own water (even though the only place we’ve actually seen people carrying water is India).

In the end, I decided I’d rather spend my time doing the cooking, cleaning, and laundry myself, rather than ineffectively pantomiming instructions. My solution was to go retro: now I clean the bathrooms and scrub the floors. I wash our clothes by hand on the rooftop and hang them on the line. I cook our meals from scratch and wash the dishes. And at the end of the day my nails are shot, but I have a feeling of satisfaction, rather than the sinking feeling of a day lost to infuriating interruptions and miscommunications.

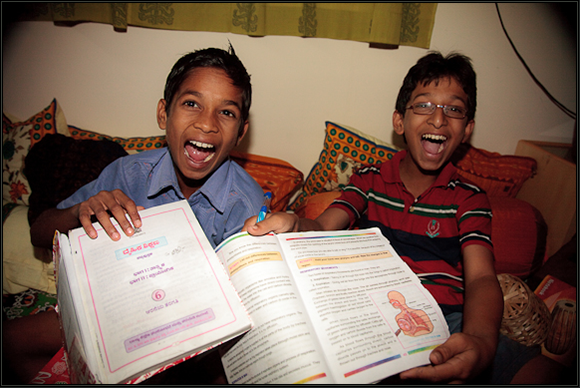

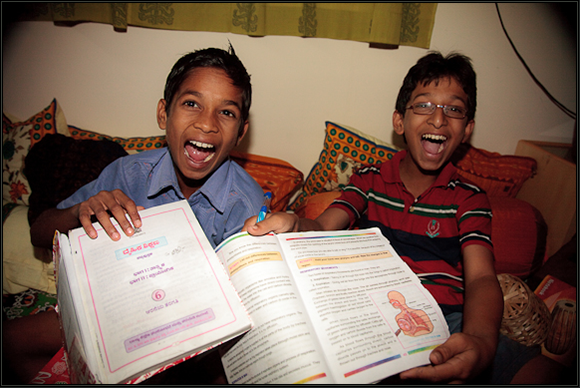

But, as it turns out, India abhors a vacuum, and there is no such thing as alone, or any approximation of it. Our new neighborhood came with children, two in particular: Sachin and Viresh. I don’t have a favorite, but I do have a least favorite…

.

“Did you just wake up, Auntie? I got up at 5:30, Auntie,” Sachin says.

“Why do you sleep so late, Auntie? What are you having for breakfast, Auntie? My father gave me four hundred rupees yesterday, Auntie,” he says and shoves the cash in my face as I’m pouring hot water into the teapot.

“What are you going to do with the money?” I ask, and resist the urge to suggest he buy a muzzle.

He shrugs his shoulders. Actually, he shrugs his whole body, and begins to hop up and down. He pops another candy in his mouth and I see his pockets are bulging with candy. Candy in purple wrappers, the same purple wrappers that I find up on my stairwell every day.

I grab his hand:

“These wrappers,” I say, “go in the trashcan.”

“Yes Auntie. What is this, Auntie?”

“A flea collar.”

“Whose boots are these?”

“Uncle’s.”

Sachin slips them on his feet.

“Auntie, Uncle’s feet are huge!”

He then starts singing:

“Boots, boots, boots, Uncle’s boots, Uncle’s boots, boots, boots. Do you play football, Auntie? I play football and cricket. These are Uncle’s shoes, boots, boots, boots…”

Damn, this kid is bored, bored out of his mind. At home, a kid his age would have soccer practice three times a week and hours of homework every evening; they’d be taking clarinet lessons, or at the very least be wasting their afternoon in front of the TV like we did when we were kids. I’m glad he’s not doing that, but I have mixed feelings about what he is doing instead.

“Kali, come here, Kali come here,” he is repeating, sort of like a chant, not really addressing the dog, or anyone else, just talking to hear himself talk, or to prove he exists, like boys that age write their name all over everything. This boy is scribbling his name all over the inside of my head. He is a verbal graffiti artist and I want to have him arrested, but this is India, where the only way to get arrested is to piss off someone rich.

He tries to teach the dog to talk:

“Kali, these are boots, boots, bo-o-o-ots,” he says, not daunted by the fact that she isn’t catching on.

He puts on my shoes and starts dancing around the living room, complaining that his feet are slipping out of them. He hums and sings and hoots and beeps while he’s dancing, he makes every stray thought into a song.

“The chair is red, the TV is rented. Kali, Kali, Kali.”

He doesn’t know how to be quiet, and I don’t know how to shut him up. The only thing to do is to kick him out, which is when he pretends he doesn’t understand my strange accent.

Then, Sachin gets distracted by a vendor’s song coming from down in the street.

“He’s selling plastic suitcases, Auntie. Would you like to buy a plastic suitcase? We bought one three years past, very good plastic suitcase.”

Shopping can always get my attention, and the plastic suitcases I’m picturing in my head are strange and fantastic, brightly colored, angular, covered with decorative stickers in an unintelligible squiggly language. I pull myself from the computer to see these very nice plastic suitcases. I peer over the balcony with my chatty shadow by my side.

“See auntie, suitcases!”

What I see is a thin man with a two-foot tower of blankets balanced on his head. The blankets are wrapped in zippered plastic covers, or “suitcases,” as they are called in my neighborhood.

.

Yesterday, Viresh, the quieter child, was outside on the balcony with Kali, and I was on the couch writing. I heard the familiar soft rhythmic bells that I’ve come to know is the sound of the camel that comes through our neighborhood from time to time.

“Auntie, look, look!”

I get up and dash to the railing, because there is a camel walking down our street. A camel! Half of Viresh’s little body is flung over the metal railing, and he is pointing with his whole being, sparks are practically shooting out of his fingertips. But he isn’t pointing at the camel.

“Look, Auntie, pizza, pizza!”

He’s pointing at a flyer that someone in a uniform has just slipped under the windshield wiper of the car across the street. He doesn’t even notice the camel that is draped in colorful blankets and bells, with a seat balancing on its hump, and children balancing on the seat.

A young boy of about twelve walks the great beast with a rope. He stops at the car with the pizza flyer on it, looks at his reflection in the side mirror, and writes his name in the dust on the window.